|

11th July to 4th

August

Syria – "Please tell Tony Blair"

Five days into Syria, at a

grazing stop in the village of Al Maharousa, a smiling man, Ghias,

came over for a chat. “How do you find the Syrian people?” he asked.

We told him our experiences of the previous five days: roadside

fruit sellers handing us peaches and apples as we passed; people in

cars winding down their windows and giving us bottles of cold water;

men rushing out of their houses to offer water for the horses;

families bringing us pots of tea at lunchtime; shopkeepers refusing

to accept payment for food; a man offering his house for a shower

and clothes washing; a woman insisting we stay at her house all

afternoon and night; people stopping their cars or motorbikes just

to ask if we needed any help.

I could go on but there’s a problem.

I’ve banged on so much about the hospitality in other countries, how

can I possibly convince you that in Syria it’s on yet another,

higher level altogether? Why weren’t we prepared for this? Syrian

hospitality is legendary - Lisa had even experienced it before - but

somehow in our heads this knowledge had become buried and obscured

by more recent, media-fed inputs: Syria as a ‘rogue state’, Syrian

troops and spies in Lebanon, Syria ‘harbouring terrorists’, Syria

aiding insurgents in Iraq…a whole series of negative images. What’s

more, with Syria’s rightfully strong opposition to the war in Iraq

we thought there might be some resentment of Britain. But these

things are all to do with governments, our experience all to do with

people.

After relating these experiences to Ghias, he smiled even more. “Will you

please tell Tony Blair?” he asked. Later that evening, over a meal

with Ghias – and his brothers, sisters, brothers-in-law,

sisters-in-law, uncles, aunts, cousins, father, mother and assorted

friends – we were talking with Sami, who teaches English in the

local school. He would love to come to Britain but is afraid. He’d

heard that men are shot in London just for speaking Arabic, that

every Arab is considered a criminal there. Other than apologise,

there wasn’t much we could do about Blair but we tried to give some

reassurance that the British people aren’t all bad. We promised to

help Sami get a visa if we can. He’s studied Dickens and knows that

London is a foggy city. What a shame if he didn’t visit for fear of

being shot.

To enter Syria we’d chosen a quiet border post up in the Yayladag

mountains. But this didn’t prevent there being a Mr Big to report

to. I could tell he was Mr Big because his Mr

Big office covered

about half an acre, his huge Mr Big leather swivel chair was set up

on a raised platform behind his colossal Mr Big desk and, although

no further clues were necessary, there was a polished gold plaque on

his door saying ‘Center President’. He wanted to know everything,

including how we intended getting the horses back to Britanya.

“Probably either ship or plane”, I said. “Ship is better,” replied

the President, “in plane there is no oxygen, this is problem for

horse”. Before he had time to start worrying that the horses might

just push us over our baggage allowance as well, I thanked him for

his advice, made my excuses and left. Big office covered

about half an acre, his huge Mr Big leather swivel chair was set up

on a raised platform behind his colossal Mr Big desk and, although

no further clues were necessary, there was a polished gold plaque on

his door saying ‘Center President’. He wanted to know everything,

including how we intended getting the horses back to Britanya.

“Probably either ship or plane”, I said. “Ship is better,” replied

the President, “in plane there is no oxygen, this is problem for

horse”. Before he had time to start worrying that the horses might

just push us over our baggage allowance as well, I thanked him for

his advice, made my excuses and left.

A couple of hours later the vet arrived and looked over our horse health

paper. All we’d been able to get from Turkey was a one paragraph

letter in Turkish. Lisa had found a translator who gave us a copy in

Arabic but not English; we had no idea what it said. The vet spoke

some English and he was able to enlighten us: “Horses very healthy

with no tumours.” Marvellous. The vet knew this didn’t exactly

amount to an official health certificate but he was, as we say in

Wales, ‘a tidy bloke’ so it was all smiles and we were in. Just

after the border we were overtaken by a tour bus with blackened out windows and a giant slogan on the side: “See Life of World in Real

Eyes.” Oh well, there’s always next year. For now we’ll have to

settle for seeing it through real ears (chestnut and hairy).

windows and a giant slogan on the side: “See Life of World in Real

Eyes.” Oh well, there’s always next year. For now we’ll have to

settle for seeing it through real ears (chestnut and hairy).

We spent our first few Syrian days more or less lost in the Jebel an

Nusayriyah mountains. The hurdle of another border had been jumped

and now we had the good prospect of having a whole new country ahead

of us. But things just weren’t the same without Audin. He’d carried

Lisa for 5,000 miles and now he was gone she was missing him…badly.

Hannah was going well but she wasn’t Lisa’s horse, she wasn’t her

Audin. We’ve had good times and hard times all along but now the

good weren’t as good because Audin should have been there to share

them and the hard were, well, just harder, harder to deal with.

After a lunchtime summit meeting under a huge fig tree, we agree to

continue at least as far as the Krak des Chevaliers and from there

either head west to the coast at Tartus where we’d heard there was a

ferry to Cyprus or, if we felt any better, carry on south as

planned.

Talking of planning, how is it that we managed to find ourselves crossing

the Carpathians and Balkans in the depths of winter and now, now

it’s the middle of July,

we’ve ended up in Syria? It takes years of

preparation to plan things as cunningly as that. The heat meant a

change of routine. Now we were rising at five, getting going as soon

as possible, crashing out under a tree from midday till about three

or four, then carrying on for a couple of hours in the more

civilized evening temperatures. Staying up late talking with our

hosts meant that a lunchtime siesta was now compulsory to avoid

building up a sleep deficit. This was just fine by me, and even

accepted by Lisa, providing we took it in turns so one of us could

keep an eye on the mares. The important thing in these situations

is, on waking up, rubbing eyes etc, to vigorously deny having

actually had any real sleep and dismiss as utter nonsense any claims

that snoring had been heard and that people who are awake don’t

snore. we’ve ended up in Syria? It takes years of

preparation to plan things as cunningly as that. The heat meant a

change of routine. Now we were rising at five, getting going as soon

as possible, crashing out under a tree from midday till about three

or four, then carrying on for a couple of hours in the more

civilized evening temperatures. Staying up late talking with our

hosts meant that a lunchtime siesta was now compulsory to avoid

building up a sleep deficit. This was just fine by me, and even

accepted by Lisa, providing we took it in turns so one of us could

keep an eye on the mares. The important thing in these situations

is, on waking up, rubbing eyes etc, to vigorously deny having

actually had any real sleep and dismiss as utter nonsense any claims

that snoring had been heard and that people who are awake don’t

snore.

At times we’d be woken even earlier than five. The mosque in the village

of Dweezah possesses the Arab world’s loudest loudspeaker system –

it’s possible that the volume control had once jammed on its maximum

setting and nobody had ever been found who could fix it. Maybe it

was just because we were camping right under the minaret. At four

thirty a.m. “Allah hu akbar etc” at five hundred megadecibels killed

off any chance of further sleep. But we forgave the man behind the

voice when he popped out later on with a pot of delicious coffee for

us. It’s strange but the familiarity and routine of the muezzin

(call to prayer) becomes quite comforting after a while. a pot of delicious coffee for

us. It’s strange but the familiarity and routine of the muezzin

(call to prayer) becomes quite comforting after a while.

A long steep drop out of the mountains landed us on the broad plain of Al

Ghab. The hills beyond are red earth dry but the plain is packed

with crops, watered by the Orontes River. We rode along the banks of

irrigation canals where Bedouin families camped and grazed their

sheep and goats on the stubble. A shepherd ran over to us, pointing

at Sealeah and asking “aseel? aseel? (purebred?)” “Yes,” we

answered, and then, pointing to Hannah “and she’s half aseel.” From

here onwards, this conversation was to be repeated several times a

day.

We felt a tiny bit sorry for Hannah only being a ‘half’ and Sealeah, like

the princess that she thinks she is, getting all the praise. Farmers

across Europe had admired Hannah for her greater power and obvious

rear-end strength (i.e. fat arse) but here it was Sealeah’s classic

Arabian beauty that struck a chord. Both of them trace back in

several lines to horses bred in the Syrian desert and bought by the

Blunts (founders of the famous Crabbet Arabian Stud) at the end of

the nineteenth century. It may be over a hundred years since horse

breeding declined among the desert tribes but after thousands of

years of partnership the memories clearly don’t die easily.

Halfway down Al Ghab we reached the ruins of the ancient city of Afamea

and decided to stop for a half day rest and soak up the atmosphere.

The place is all open and we were allowed to camp behind a café bang

in the middle of the site. The main feature is a two kilometre long

colonnaded street running north to south, a street which Anthony and

Cleopatra once travelled on their way back from some

Armenian-bashing up north. But despite all the history we will

always remember this place for one thing above all others: The Great

Fire of Afamea.

We had finally sat down after a couple of hours of setting up camp,

making a safe pen for the horses and getting food supplies from the

village. We smelt smoke but assumed it was just a controlled fire,

someone burning rubbish maybe. But very rapidly, the smoke became

thicker and started stinging our eyes. A man came running from

behind the building, shouting that we must move. In seconds flames

appeared round the corner and reached the edge of the horses’

electric pen – a strong gusty wind was blowing the fire through

parched dead grass at frightening speed. The fire had been going on

behind us and the high wall had kept it hidden from view. Lisa

immediately led the horses away to safety but the next few minutes

for me were just a blur of flames and smoke and panic as I

desperately tried to rescue our tent, saddles, saddlebags, clothes,

all our precious equipment.

Our camp was against the outer wall of a courtyard and just around the

corner of the wall was out of the wind and safe from the flames.

Each run to grab a saddle or a bag became harder as the heat and

smoke intensified. All our money, passports and papers were in the

tent but the tent had been tied tightly to the wall due to the

strong wind. With the flames only yards from the tent there was no

time to fiddle with knots. I pulled but it wouldn’t budge. Now I was

really worried and the heat was unbearable. I pulled harder, poles

snapped, fabric ripped but at last the guy ropes gave way and the

tent came free. I ran to safety, dragging it behind me and bent over

coughing, lungs burning. Some things were still left behind but now

it was too late, in a matter of minutes the fire had burned out our

whole camp area.

When the last flames had finally been extinguished, I assessed the

damage: tent poles snapped and fabric torn, all Lisa’s spare clothes

burnt, collapsible water buckets melted into goo, Sealeah’s numnah

melted, electric fence burnt and poles bent. Virtually everything

else was UHT (ultra heat treated) but remarkably there was no other

serious damage. I had singed hair on my head, eyebrows and arms and

my fingers were burned from pulling the hot nylon guy ropes. I went

over to find Lisa. The horses were oblivious to it all and calm as

anything; they thought they’d just been led out for a graze. I

couldn’t understand why I wasn’t feeling more annoyed about the

damage but Lisa voiced what we were both thinking: the horses were

safe, what else mattered? Compared to losing Audin, this was just a

minor hiccup.

At sunset we rode Hannah and Sealeah around the ruins of Afamea, down the

full length of the main street from the Antioch Gate to the Damascus

Gate. In the beautiful evening light we had the whole place to

ourselves. The city had once been famous for its horses: thirty

thousand mares and three thousand stallions. The grazing must have

been a lot better two thousand years ago because now there were only

two horses here and they weren’t impressed by what was on the menu.

Sealeah kept nibbling at whatever she could find but Hannah was just

disgusted. It was no use telling her that she was in the ‘Fertile

Crescent’; she couldn’t see any proper green grass and that was

that. Their staple diet had now become straw and barley - mixed up

to become strawley – this was usually all we could find. Presenting

them with another bucket of this unappetizing stuff, we could sense

the disappointment. Where they come from straw is for shitting on,

not eating - perhaps it’s like asking us to tuck into a plate of

Kleenex. To spice it up a bit we add oil, bread and apples and

Sealeah helps herself to anything I try and sneak into my mouth as

we walk along. Remarkably, this diet has kept them going well and

they stayed in excellent condition, so much so that many people

asked us if they were in foal.

A day’s ride from Afamea took us to Al Mahourousa where Ghias had met us

on the roadside and put us up for the night. He said that we were

the first English speakers to visit his house and would probably be

the last. His father wanted us to stay for a week. But we had to

move on so we continued south, past the Assassins’ fort at Misyaf

and back up into the hills again to reach the Krak des Chevaliers, a

spectacular crusader castle. The ‘Krak’ has been described as the

finest castle in the world and it’s certainly hard to imagine a

better one. The famous Saladin never managed to capture it and a

small band of crusaders hung on here to the bitter end, long after

Jerusalem had been retaken. After a few days rest camped beneath the

castle walls we were ready to carry on south. We’d almost forgotten

that we’d considered turning back from here; the incredible Syrian

friendliness and hospitality had given us a huge morale boost.

We couldn’t head due south, however, because a large lump of Lebanon lay

in the way. Unfortunately we cut it a bit fine skirting the border

area and had what is known as ‘a bit of a run-in’ with the

police…and the army. You have to be careful with Syrian maps because

they tend to show international borders where the government would

like them to be, rather than the inconvenient detail of where they

actually are. But this wasn’t the problem here, we were just

something different for the men in uniforms to get excited about. It

started mid-afternoon when an army truck stopped to check our

passports and hear our life story. Then there was a long wait at a

police checkpost while an officer appeared to be really struggling

to decipher our passports. After ten minutes Lisa put him out of his

misery by telling him he had them upside down. Another hour later we

reached yet another army post and another forced stop for passport

scrutinization. By now we’d had enough so we stopped at the next

house and asked where we could buy ‘tibin (straw) and sha-ir

(barley).’ An hour later we were nicely settled in the back garden

of the barley man’s house, having several cups of tea and discussing

international terrorism (as you do).

And then the soldiers arrived. They explained that their commanding

officer wanted to see our passports. “But we’ve shown them three

times today already!” Resistance was futile. I wasn’t happy to let

the soldiers take the passports so I had to go with them. Machine

guns were waved at a passing minibus – quite an effective hitching

technique – and forty five minutes later I was sitting in a tiny

concrete shed somewhere on the Lebanese border. Across the desk was

a grinning army officer. He did glance at the passports of course

but the real reason for dragging me out here was to practice his ‘inglizi’,

namely the numbers one to ten, hello, good…bye and good morning. But

my good morning had been a long time ago and now it was becoming a

bad evening. It was ten o’clock at night and I couldn’t stop

yawning. I was about to say “Please can I go home now?” when the

officer started writing something very carefully on a piece of paper

and pushed it over the desk to me. I read it out: “If the length of

the pendulum changes…”

Blimey! Where did that one come from? One minute we’re in Sesame Street

counting to ten, the next we’ve moved on to the laws of physics. He

was immensely proud of himself for remembering this but was very

keen for me to finish off the expression for him. “If the length of

the pendulum changes…err…it’s time to let the tourist go?” I

suggested hopefully. He shook his head. No, that wasn’t it, try

again. Just then the coffee arrived – two millilitres each and

tasting predominantly of soap – and, almost simultaneously, so did

the jeep that had been called to take me back. All talk of pendulums

was immediately forgotten and between saying “Good…Bye!” about ten

or fifteen times, the officer was all beaming smile and vigorous

not-letting-go-for-uncomfortably-long-period handshaking.

Back at the house, where Lisa was having an interesting conversation with

a woman who had twenty kids, things were just getting back to normal

after a police visit. A worried looking policeman had spent the last

hour following Lisa around the house and yard with his machine gun,

clearly terrified that he’d stumbled on something serious. Not least

among his concerns was the fact that Lisa didn’t have a passport to

show him. She tried to explain that not only had our entire

afternoon been devoted to passport-showing but also, at this very

moment, her husband was doing even more passport-showing with the

army somewhere. None of this helped much until the Big Police Chief

arrived, apologised profusely and promised that he’d inform every

police post between here and Damascus so we’d never have to

passport-show again.

A few days later, somewhere not far from the Homs to Damascus highway, we

were sitting under some trees sheltering from the midday sun. We

were quite pleased with ourselves for finding such a good hiding

place and confident of getting some top quality siesta shut-eye,

when a man on a motorbike came slaloming through the trees. “Hi, I’m

Mohammed and I’m going to be your plain-clothes police spy for

today!” Okay, those weren’t his exact words but it was the general

idea. Mo was a particularly friendly spy. He showed us a nearby

hosepipe that was irrigating some fruit trees and kindly held it

over my head thus rinsing out a few kilos of desert dust. He even

brought us each a bottle of Fanta, complete with straw. A few hours

later, back on the road, I noticed him sitting on his bike, a tiny

dot silhouetted on the hillside above us. I waved and he waved back.

What a nice, friendly, Syrian plain-clothes police spy he was!

Lisa was convinced that Mohammed’s presence was connected to her dealings

with Big Police Chief a few nights earlier. “He’s not a spy, he’s

protecting us,” she protested. “Protecting us from what?” I

answered, “dirty hair and orangeade deficiency?” It was clear,

however, that our Mo was in a very different category from your run

of the mill, bog-standard village spy. We’d come across these

individuals nearly every day and it seems that they are generally

considered to be a complete pain in the backside. On our first night

in Syria, at the village of Rabi’a, a man approached me as I was

getting water from the mosque. He wanted to see my passport so I

asked to see his police ID. This he didn’t have and it wound him up

a bit. He followed me into a shop where I had the usual Q&A session

with the assembled clientele. After a while Village Spy couldn’t

contain himself any longer and butted in, demanding to know my and

“madam’s” names. Very carefully he wrote ‘h a r r y’ and ‘l i s a’

down in the shopkeeper’s exercise book and then tore out the page.

This unnecessary damage to a perfectly good exercise book greatly

annoyed the shopkeeper who then had a real go at Spy, stopping just

short of giving him a slap (this seems to be the preferred method of

combat in most arguments we’ve witnessed). We later observed a

similar level of respect accorded to many other village spies.

After

a couple of days heading south towards Damascus, we worked our way back

up into some hills. These were called the ‘Jibal Lubnan Ash Shaqiyeh’

on one of our maps and ‘Anti-Lebanon’ on the other. We thought it was

Lebanon that was anti-Syria but here was a whole mountain range

expressing nationalist rivalry. Nestled in a rocky gap in these hills

is the pretty village of Maalula, notable for being one of only three

remaining villages where Aramaic – the language spoken by Jesus – is

still in use.

Here we stayed at an under-construction dairy farm which had just

acquired a few cows to get things started. The cowmen were speaking

Aramaic as first language and they taught us a few words. It sounded

very lispy (lithby) to us and tricky to follow. We then had a moment

of pure enlightenment. Of course! This must have been why Jesus’

“blessed are the peacemakers” from his sermon on the mount was

famously misheard as “blessed are the cheesemakers”! And later

interpreted by some scholars as not being intended to be taken in a

literal sense but to actually refer to all manufacturers of dairy

products. And to think, we’d made this startling discovery while

staying on a dairy farm in the holy land! How travel broadens the

mind.

Next stop after Maalula was Saydnayya, a Christian town with an imposing

convent built on a rock and no fewer than forty other churches to

choose from. Damascus was just a short hop away by bus so we took a

few days rest to get the ball rolling on horse health certificates

for Jordan. The highlight of Lisa’s day in Damascus was accidentally

walking into the Ba’ath Party Headquarters and not being allowed to

leave! Not until she’d been given a nice cup of coffee and had a

good chat with the friendly Ba’athists anyway.

We descended from Saydnayya into a hot dustbowl of quarries and

factories, highways and towns – not exactly idyllic riding country.

To make matters worse, the towns were full of screaming boys,

running along beside us. “Arabi aseel? (purebred Arabian)” they’d

ask, pointing at Sealeah. The shouts would then ripple back through

the ranks. “Arabi aseel arabi aseel arabi aseel!” Unfortunately all

the shouting and running and bikes and bodies darting about upset

the horses. Even worse, a stone would occasionally be thrown and

we’d have to stop and chase all the kids back.

Luckily this area gave way to a much quieter region between Damascus and

the Jordanian border. It appeared to be one huge desert military

zone with camps and tanks, jeeps and soldiers everywhere. But the

tank tracks were firm and clear of rocks, giving us some superb long

canters. Our greater speed meant that all too soon, we found that

Syria was running out. On our last night we had a lively evening

with a woman, her seven young kids and as many people from the

surrounding Bedouin tents that could cram into the one room house.

The woman’s husband had recently died and she couldn’t prevent her

tears when she showed Lisa his photograph. But she and all her kids

were delighted that we were staying with them for a night. As always

in Syria we were made to feel as though we’d done them a big favour,

not the other way round. Is there a country on earth with friendlier

people than this?

Even all the ‘special’ police who stopped us nearly every day were

friendly. These gentlemen of the SARPD (Syrian Arab Republic

Political Department) were always happy to take down only our first

names, as long as we provided our mother and father’s names as well.

Across Syria, from north to south, there are now some thirty little

notebooks, each with a page that says “Harry John Gordon Judy Lisa

Rachel Peter Marly” (I particularly enjoyed hearing them repeat the

Marly). As long as they’re happy in their work, that’s the main

thing.

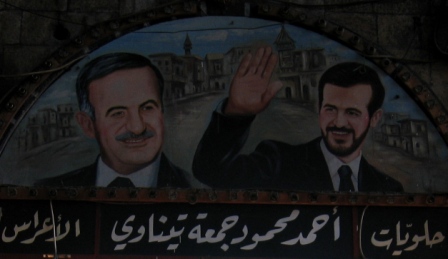

At the border we were genuinely sorry to be having to leave. A final wave

to a final portrait of President Assad with his little moustache,

our passports inspected a mere five times within two hundred yards

and we were out in no-man’s land. I haven’t even mentioned the food,

the falafel and houmus, the fresh figs, the peaches, the apples for

10p a kilo. I haven’t mentioned the man who rode past on his

motorbike and shouted “Hellooooo Misterrr Jones, how you dooooooooo?”

I haven’t mentioned that everybody in Syria rides a motorbike; a

family of five on a bike is common but three persons per bike is

about average. (There’s only one thing more worrying than seeing a

five year old kid hanging on the back of a motorbike and that’s

realizing that it’s his six year old brother who’s driving.) I

haven’t mentioned that nearly everyone in Syria told us it was “Ooh,

very far!” to the next village on our map, despite having just found

out we’d ridden from Wales. I haven’t mentioned any of these things

because Syria’s finished, we’re already in no-man’s land and

Jordan’s just up there on top of the ridge.

|